A SELCO Foundation Initiative

Sustainable Energy Innovations for Gender Inclusivity

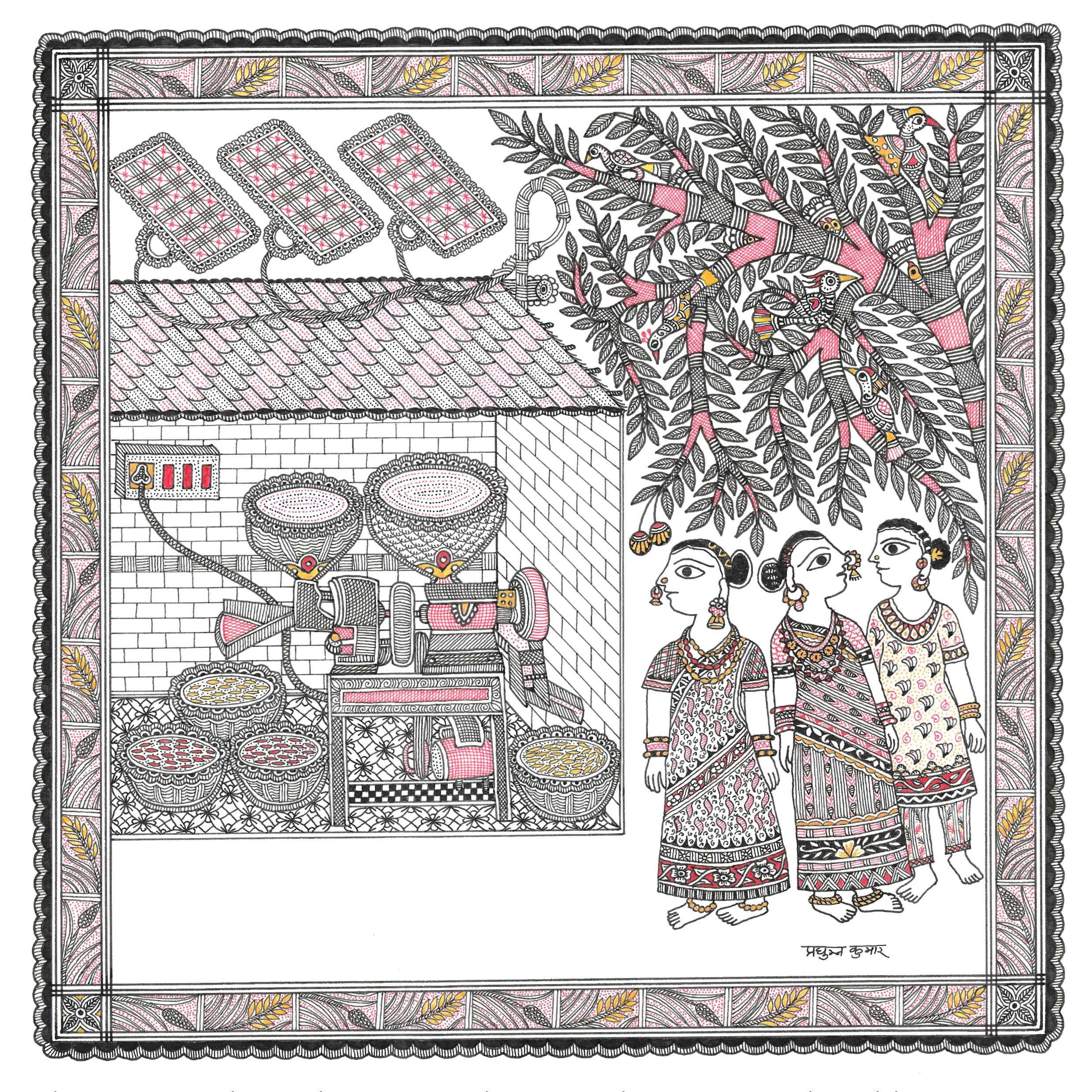

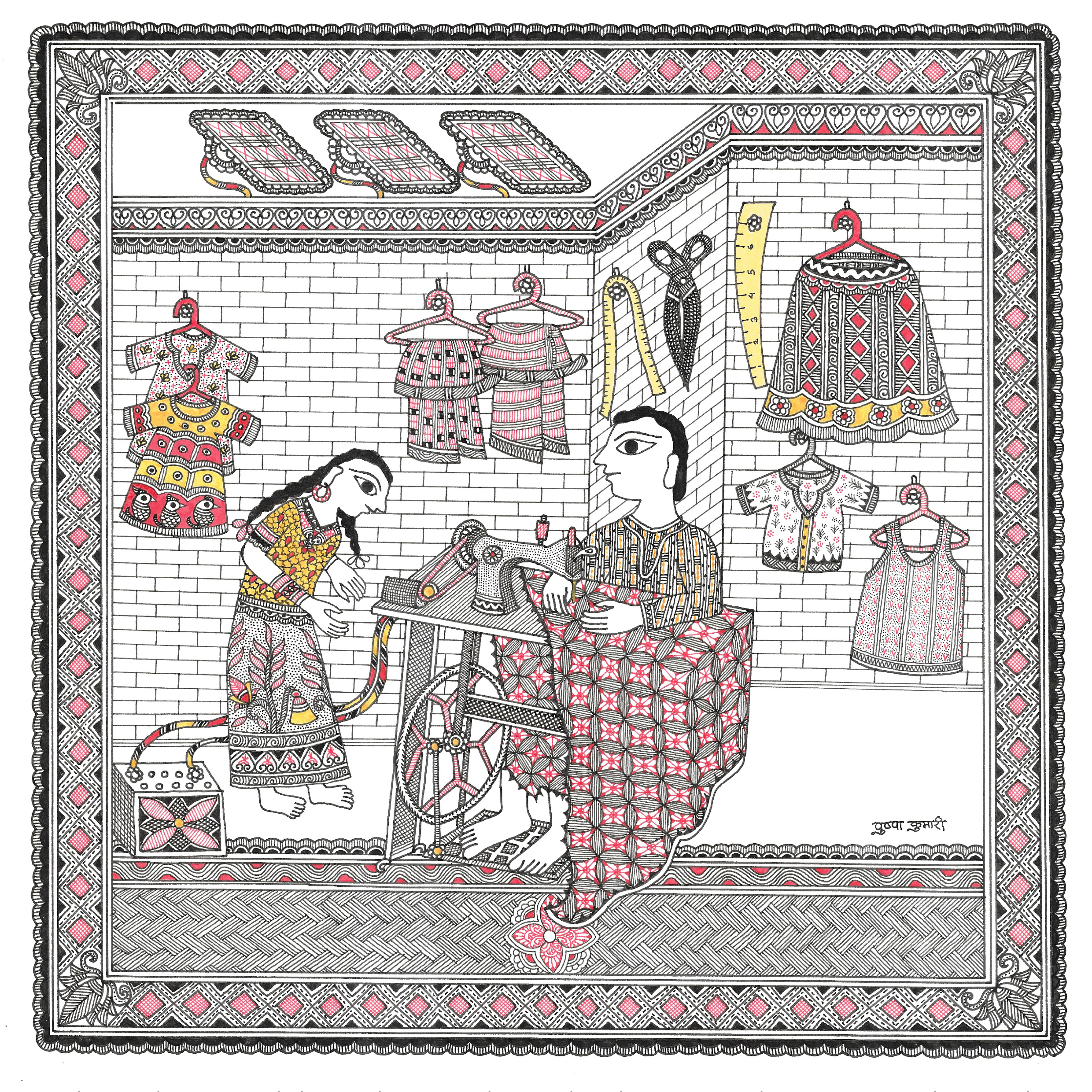

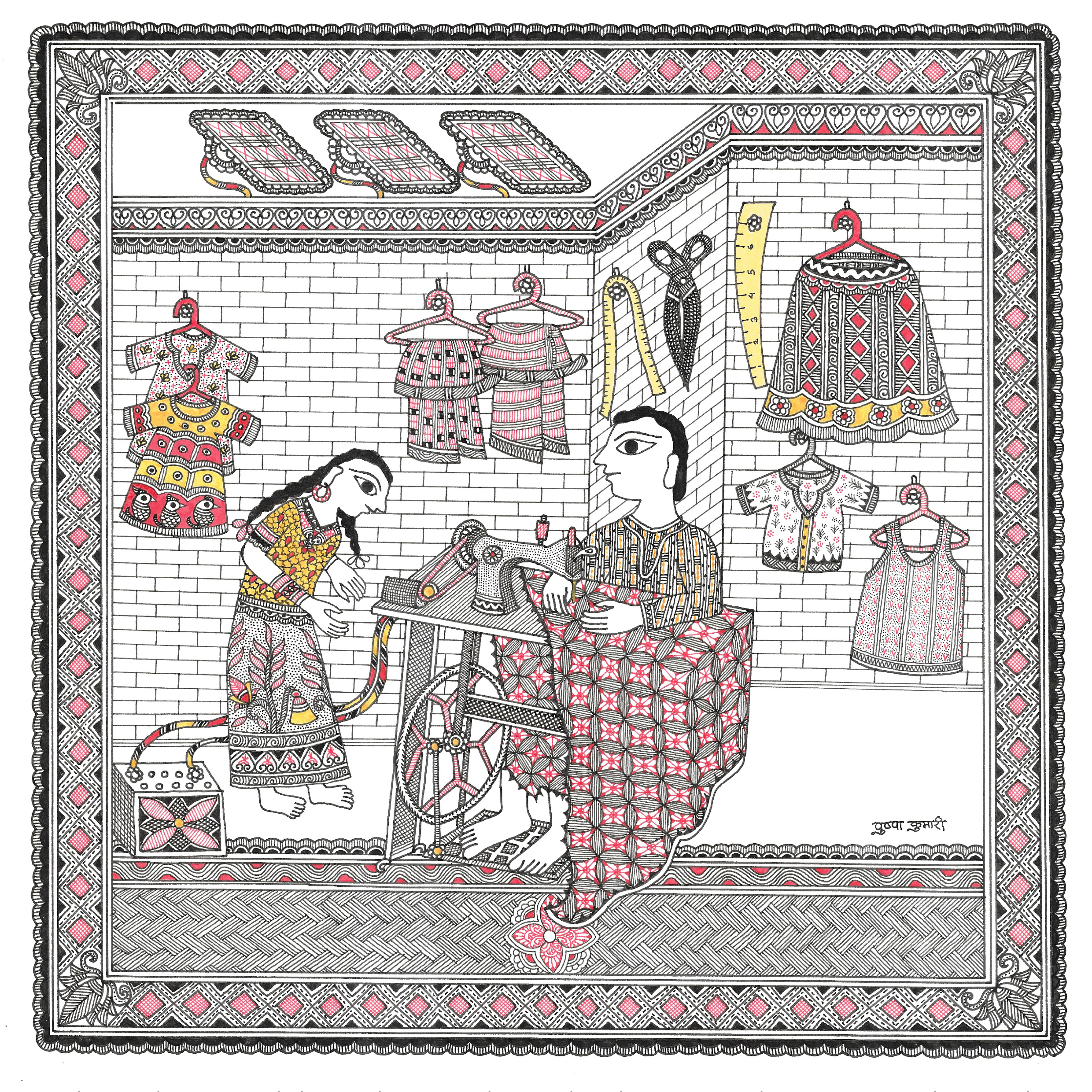

(illustrated in Madhubani)

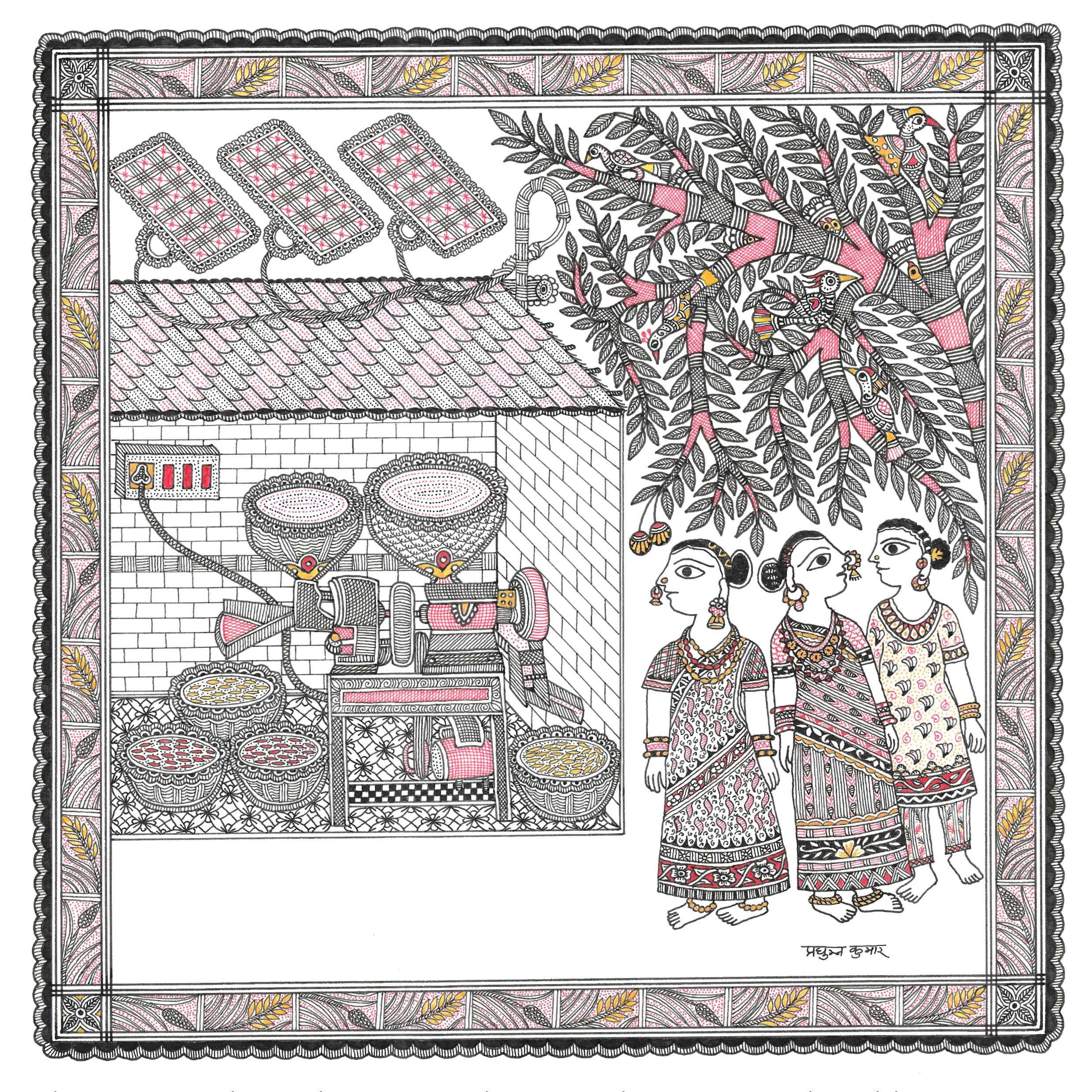

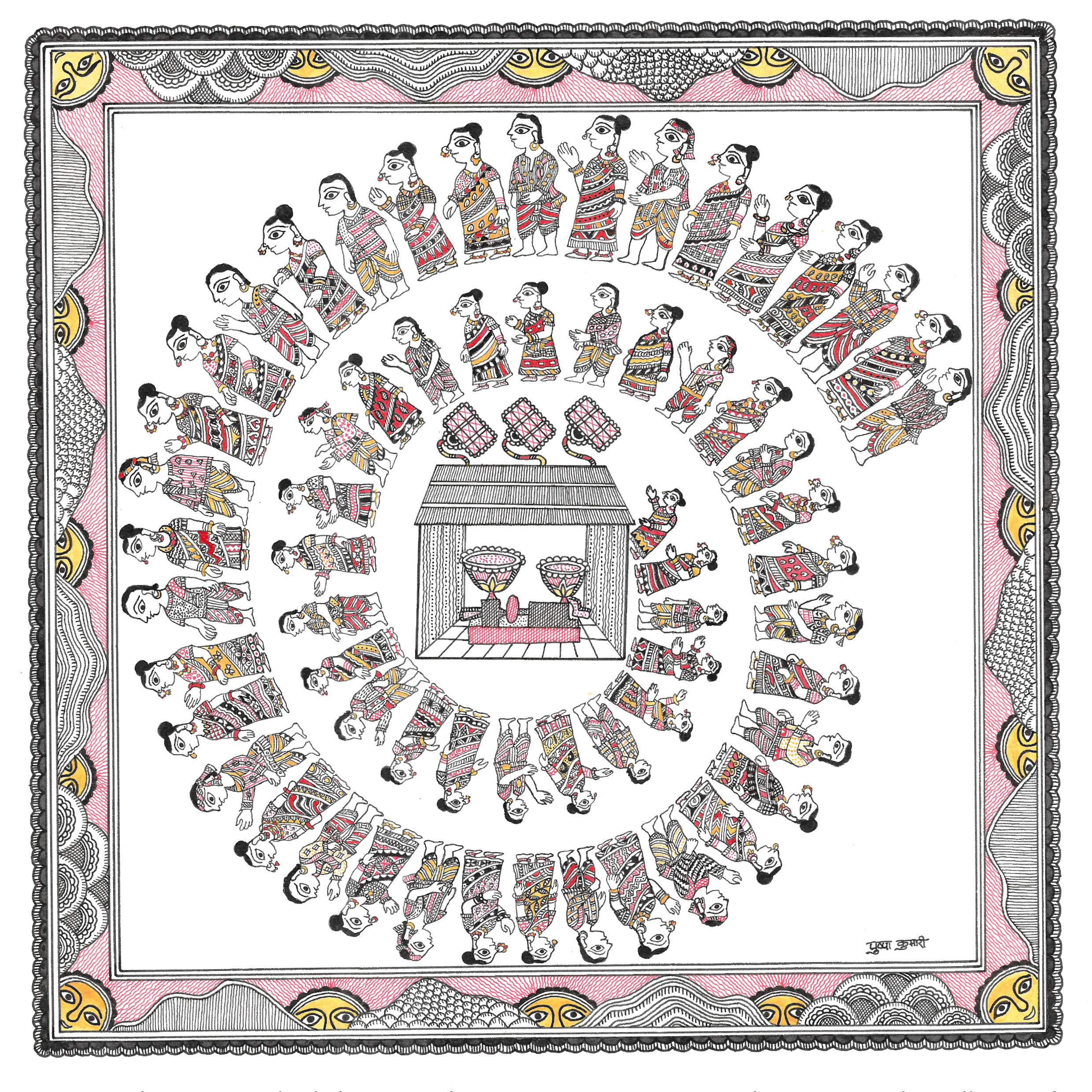

Depicts women entrepreneurs who started a decentralised rice and millet milling centre for the, later innovated other essential services for the community, & for their livelihoods. While the shops slowly resumed post the lockdown, disruptive power cuts and inaccessibility to diesel left a lot of work undone for the farmers, increasing the demand and income of the mill, while helping farmers move forward in these uncertain times.

There is a remote village in India belonging to a tribal community of farmers who predominantly grow ragi (a type of millet) and rice. This village is so remote, that people from here have to walk several kilometres across forests and mountains, just to access basic everyday services like mobile charging, photocopying or printing services for official work or even rice hulling.

This situation changed in 2019. A 27 year old farmer, her mother and the women's self-help group established a decentralised rice and millet milling centre with the help of a local NGO. The presence of the mill in their village eased the access and drudgery issues for over 500 rice cultivating farmers and 270 ragi farmers who would earlier have to travel several kilometres and spend much time and money to get basic work done. The income from this centre was equally divided amongst all members.

Apart from milling, the livelihood centre also offered other essential services such as printing, photocopying, and mobile charging - all of which were in high demand and used for school work, government documentation and other official purposes by students and teachers in the area. At the centre, the 27 year old also operated a sewing machine, using it for basic mending and embroidery for the local villagers. All of these services were solar powered and proved extremely reliable.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, with a positive case in the vicinity, many villages were under strict lockdown. Even when shops began to reopen later on, the disruptive power cuts and inaccessibility to diesel (for households and businesses who relied on generators) made it extremely difficult for farmers to get any work done. In neighbouring villages, local NGOs took it upon themselves to spread the news about the functional decentralised livelihood centre set up in a remote village. Within a few weeks people from 17 villages in a 12-15 km radius, started coming to this centre for their essential services, increasing the demand and income of the mill, while also helping farmers move forward.

The presence of solar-powered equipment in a place that experienced 12-15 hours of power cuts during the day, made the centre an extremely reliable one. New customers recognised the convenience of the livelihood centre as a one stop shop for all their needs, and continued to use it even post the lockdown period.

It also so happened that the 27 year old’s uncle who ran a tailoring unit in the nearby town, returned to her village during the lockdown. This gave her the opportunity to pick up advanced tailoring skills under the expert training of her uncle. Her successful training has led to her receiving an order to stitch all the 7th grade school uniforms for the school village as favoured by the panchayat. This new job order will increase the centre’s income multifold.

“I think this is the best solution for village communities, because farmers get milling services within a very short distance. We have been moving from village to village to share information about this solar powered ragi milling machine. Spreading the message this way has been very effective in promoting our business. Ragi is very nutritional- especially for young children, pregnant and lactating women. We also plan to start sale of ragi powder to the nearby anganwadi (Early child care) centres to ensure a supply of nutritional food for the children.” - President and Secretary of a local Self Help Group

One of the biggest challenges going forward will be the loss in risk-taking among entrepreneurs from households living in poverty. For many entrepreneurs restarting the business or taking the risk of building it again will be harder. Models building on SHGs, like the one in this story, would allow risk to be shared while also benefiting the whole community, because services are decentralised.

Madhubani by Pushpa Kumari

Kumari is a younger generation Mithila artist who has retained the Mithila paintings’ distinctive styles and conventions while addressing new subjects such as women’s rights in India.

Kumari’s works continue to draw on a strong theme of sexuality and the union between male and female. She was taught by her grandmother, the acclaimed Mithila artist Maha Sundari Devi, one of the pioneering Madhubani artists to work on paper. Selling from age 12, Pushpa’s uniqueness lies in her desire to experiment and develop new themes and treatments. She has pursued an artistic vision that derives greatly from the Madhubani tradition but which over the years, has been personalized with her own private preoccupations and quests.

Madhubani by Pradyumna Kumar

Pradhyumna Kumar, from Muzaffarpur (Bihar), is the first Indian to ever win the prestigious UNESCO Noma Concours in Japan in 2006 as well as in 2008. A surgery cost him a job of being a land surveyor, after which he took to art influenced by Madhubani traditional style improvising themes and topics of his own imagination and interest.

The works by Pradyumna Kumar are in the permanent collections at National Museums, Liverpool, UK, the Mingei International Folk Art Museum, San Diego, USA and QAGOMA, Brisbane, Australia. He is also an author/illustrator of two books- How The Firefly Got Its Light and Durva’s Bamboo Forest.

About Madhubani

The Madhubani style of painting can be traced to the Madhubani district in Bihar, literally meaning 'a forest of honey', where women spent a lot of time making these paintings on the walls of their homes. The women used their keen sense of beauty to create evocative paintings of gods and goddesses, animals and characters from mythology, using natural dyes and pigments and painted with the help of twigs, fingers and matchsticks.